I work in business development for an energy company. So, I spend my time thinking about business opportunities in the space, and of course, the “carbon transition” has taken up an inordinate amount of headspace lately.

But what is striking to me, in doing research and reading all the news about it, is the level of confusion about how to think about these opportunities. In the past I’ve posted on Twitter or LinkedIn on this sort of thing, but with this personal website now stood up, I figured this may be an interesting topic for my inaugural post.

We’ll start with what I think is the flaw in current thinking, before outlining what I consider a more grounded framework for evaluating opportunities.

Top Down Thinking

It’s illustrative that Shell – arguably the single most progressive integrated oil company with respect to climate ambitions – would punt $7 billion back to investors after selling its Permian assets, rather than put that capital to work earning returns from a carbon transition strategy.

That move speaks, loudly, to a corporate actor that is confounded about the opportunity set and the path forward on the carbon transition. And Shell is far from alone. There are many more companies that are instead putting good money after bad in renewable energy, sustainable finance, cleantech, and so on.

It’s all for a good cause, no doubt, but if we zoom out, what we perceive is a genuinely heartwarming outpouring of well-meaning intentions, crowding narrowly into a preponderance of business ideas that just don’t make sense in any conventional manner of thinking.

What is causing this confusion?

At its core, the problem is top-down thinking based on policy aspirations. We see this all the time with the “if-then transition wedge graph.”

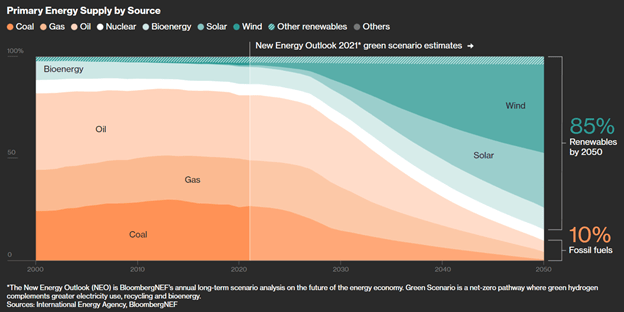

Here’s an example, from Bloomberg:

In this mode of thinking, one runs a scenario analysis on what new energy mix would be required to achieve some emissions target (e.g. “net-zero by 2050,” as in the example here).

The mistake is in confusing these aspirational policy outcomes with market forecasts. In the graph above, the ~35% market share captured by solar in 2050 is merely a guess at one potential climate solution. The dependencies required to get there are glossed over. Left unanswered is the key question: what economic and regulatory imperatives are going to compel this business activity?

Building a business strategy around these types of “forecasts” is magical thinking.

A Clearer Framework

Here is my overarching thesis: instead of focusing on aspirations (“in order to achieve X, society will need Y”), one needs to understand that there are, alone or in combination, three primary drivers behind any carbon transition opportunity:

Creating commercial value (“Y has value”);

Complying with government mandates (“Y is now law / the government will pay for Y”); and

Satisfying altruistic imperatives (“Y is charity / branding”).

These drivers fall out of the foundational climate issue. One the one hand, we have an energy sector which serves a basic and enormous societal function – it is and always has been value creating, and as essential to civilization as water.

But on the other hand, humanity’s use of that same energy system has produced a massive negative externality in the form of climate change. The “carbon transition” writ large has a dual function: change the underlying energy system to make it less emissions intensive and mitigate the climate change externality.

Value Creation

In the context of the transition, “value creation” thus relates to energy solutions that can create value versus competing alternatives yet are also, coincidentally, low-carbon or emission-free.

For example, hydroelectric power. It can be competitive on a dollar-per-megawatt hour compared to natural gas, but is also lower emissions on a lifecycle basis. Or, ethanol as a gasoline blendstock. It can enhance octane, up to a limit, but is also produced from corn, which naturally sequesters carbon dioxide.

Pursuing business opportunities around traditional value creation strategies is relatively safe ground. But, if the climate externality could have been solved by profitable value creation alone – that is, without any external intervention – then we would not be in this situation in the first place. It’s just important to recognize that this is a limited subset of opportunities, and that one must not confuse other drivers with this one.

Government Mandates

Contrast the profit motive with governmental mandates around climate change. These policies are not directed towards creating new value propositions in the energy space as a first order objective, but rather reducing the carbon intensity and emissions profile of the energy sector. They can take numerous forms: prescriptive and performance-based regulations, taxes, subsidies, targeted procurement, research & development initiatives, and outright investments.

The business cases that fall out of these programs are just as numerous and diverse: selling light-duty electric vehicles instead of internal combustion engines to generate regulatory credits; developing carbon capture and sequestration facilities to capture 45Q tax credits; offering into Department of Defense procurement programs for renewable energy; obtaining national laboratory funding for small scale nuclear reactors; and so on.

These are all examples of legitimate business opportunities. But the game plan would not be to compete on value with conventional, fossil energy products. Rather, it would be to capture some edge that a regulatory body has thrown onto the field as a restriction or incentive.

The dependencies are thus vastly different, as are the risks.

Voluntary Action: The Altruistic Imperative

What about private actors taking voluntary action? For example, Amazon voluntarily purchasing renewable power for its data centers. Voluntary action involves an individual or business paying for a “green” product that has little or no marginal utility versus the next best “non-green” alternative, even when there is no regulatory agent compelling them do so.

The imperative is instead altruistic. The purchaser is doing this to “make the world a better place,” or, to signal that intent to others. In other words, this is charity, where the charitable recipient is ultimately intended to be the “environment.”

There is nothing wrong with donating to charity of course, and charity is big business: something on the order of 2.5% of GDP – $450 billion plus – goes to charity every year in the US alone.

In some instances, the altruistic imperative may be more self-serving. A brand with a progressive customer base and progressive management team – Ben & Jerry’s or North Face – may recognize that its sales depend heavily on image and not necessarily product quality, and that image must include a social agenda.

Or take financial institutions, still licking their wounds after the financial crisis, and concerned about their “social license to operate.” In this context, the “green finance” space has gone parabolic.

An example is the investor who is giving Enbridge a fifteen to twenty-basis-point discount on their “sustainably-linked bond” offering. The underlying risk profile of the bond itself does not warrant the lower yield, so the investor is essentially giving this value away. The investor is not mandated by the SEC to do such a thing. It’s charity.

In business cases underpinned by this altruistic imperative, as in all charitable enterprises, price formation is highly obscure and thus risky. There is no “next-best” utility proposition as with a free market value case. Nor is there a fixed-dollar or limited-volume regulatory credit to sell or buy for compliance reasons. Forecasting demand and building a revenue case in such an environment can be fraught.

Voluntary Action Which Looks Regulatory

We should note there are other cases where the altruistic behavior can assume the character of regulatory action, or where the voluntary action is done in anticipation of regulation.

For example, the CORSIA program instituted by the airline trade group IATA will require airlines to procure carbon offsets for flight emissions. Once in place, this program would look quite similar to a governmentally mandated cap-and-trade program.

Ex-post, the “compelling imperative” would be legal in nature – it’s a binding contract. Penalties for breach would be civil, not criminal, but still, it has the force of law. Building a business case around such an ex-post voluntary commitment is much different than one dependent on an ex-ante expectation of a voluntary commitment.

In yet other cases of voluntary action, private actors endeavor to proactively front-run regulatory action. An example might be the “One Future” coalition of natural gas operators voluntarily reducing fugitive methane emissions. Those companies know to expect legislation on methane (it’s coming!) and are attempting to control both the narrative and to manage the regulatory agenda, as well as profit from early mover advantage.

From a risk perspective, these types of voluntary actions have the look and feel of the regulatory imperative, although one should be very careful in understanding that the driver is much weaker and subject to change.

Towards Better Evaluation

We’ve walked through one of the bigger flaws in thinking about the carbon transition and stepped through the three true drivers of opportunities: value creation, regulatory mandates, and the altruistic imperative.

To what extent any particular opportunity leans on one or more of these drivers will govern how one should structure the strategy approach to the opportunity, as well as how one should evaluate the risk of the business.

Hopefully we’ll have more to come where we examine market activity through this lens. Meantime, thanks for reading, and please feel free to comment below, or at least until I turn them off!